According to a World Bank report, Kazakhstan could increase its national income by 27% if the country closed the gender wage gap, QazMonitor reports.

Wages of working women around the world on average is about 80% of men’s wages but in Central Asia, the figure is lower.

Kazakh women earn only 78% of men’s wages. In Tajikistan, women are paid only about 60% of what men earn, while this figure is 61% in Uzbekistan, and 75% in the Kyrgyzstan.

The report notes that countries with higher levels of gender equality – where women can contribute fully to the diversification of the workforce – enjoy a higher income per person, resulting in faster economic growth.

“If women across Central Asia were to participate in equal measure to men, national income would be anywhere from 27% higher in Kazakhstan to 63% higher in Tajikistan. In Uzbekistan, equalizing the average wage among women and men who are already working would alone pull more than 700,000 people out of poverty,” the report said.

The World Bank’s Listening to Central Asia study surveys members of thousands of households in four countries in the region each month. According to the researchers, restrictive gender norms and social expectations prevent women from achieving much more in the labor market.

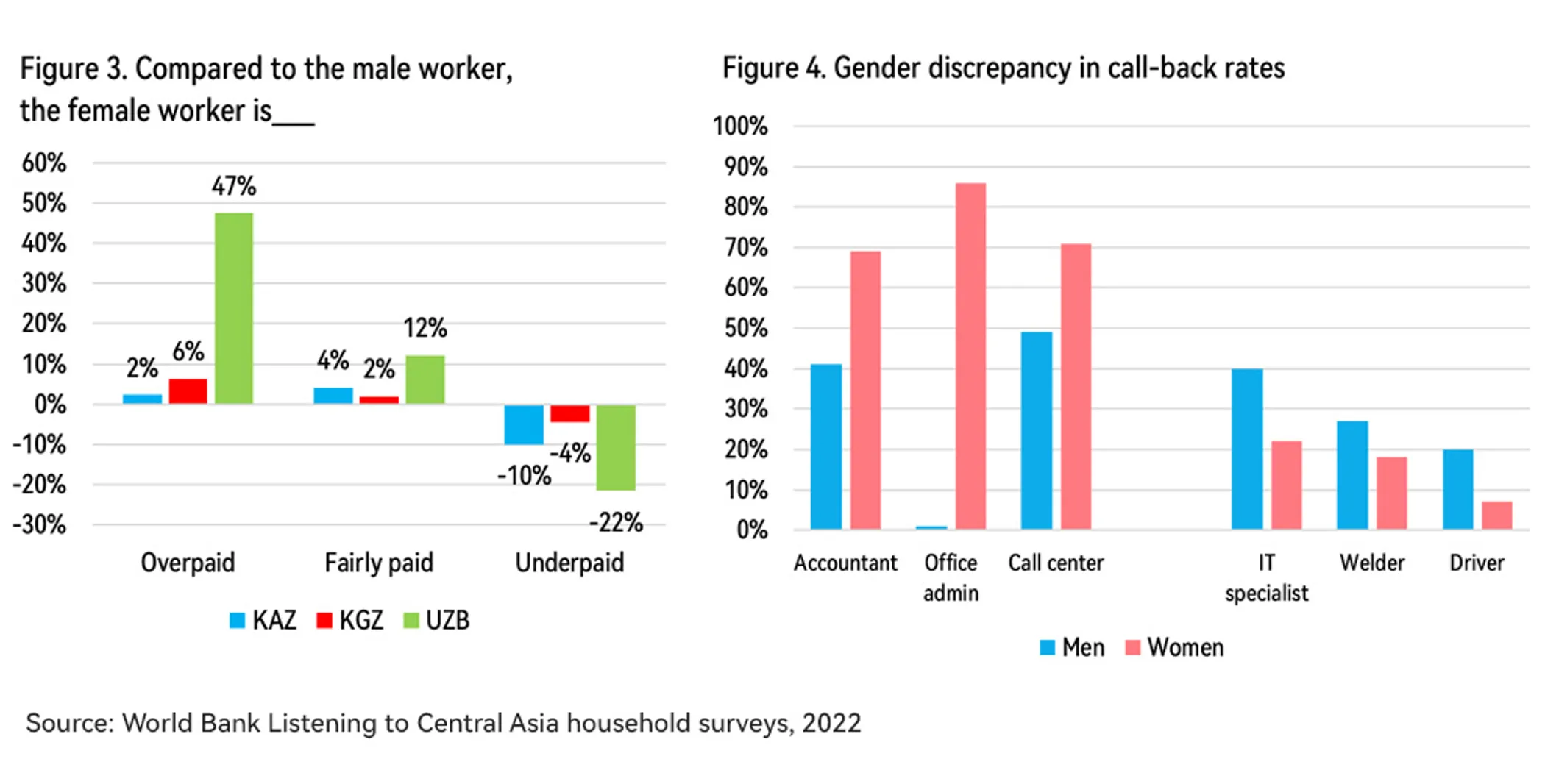

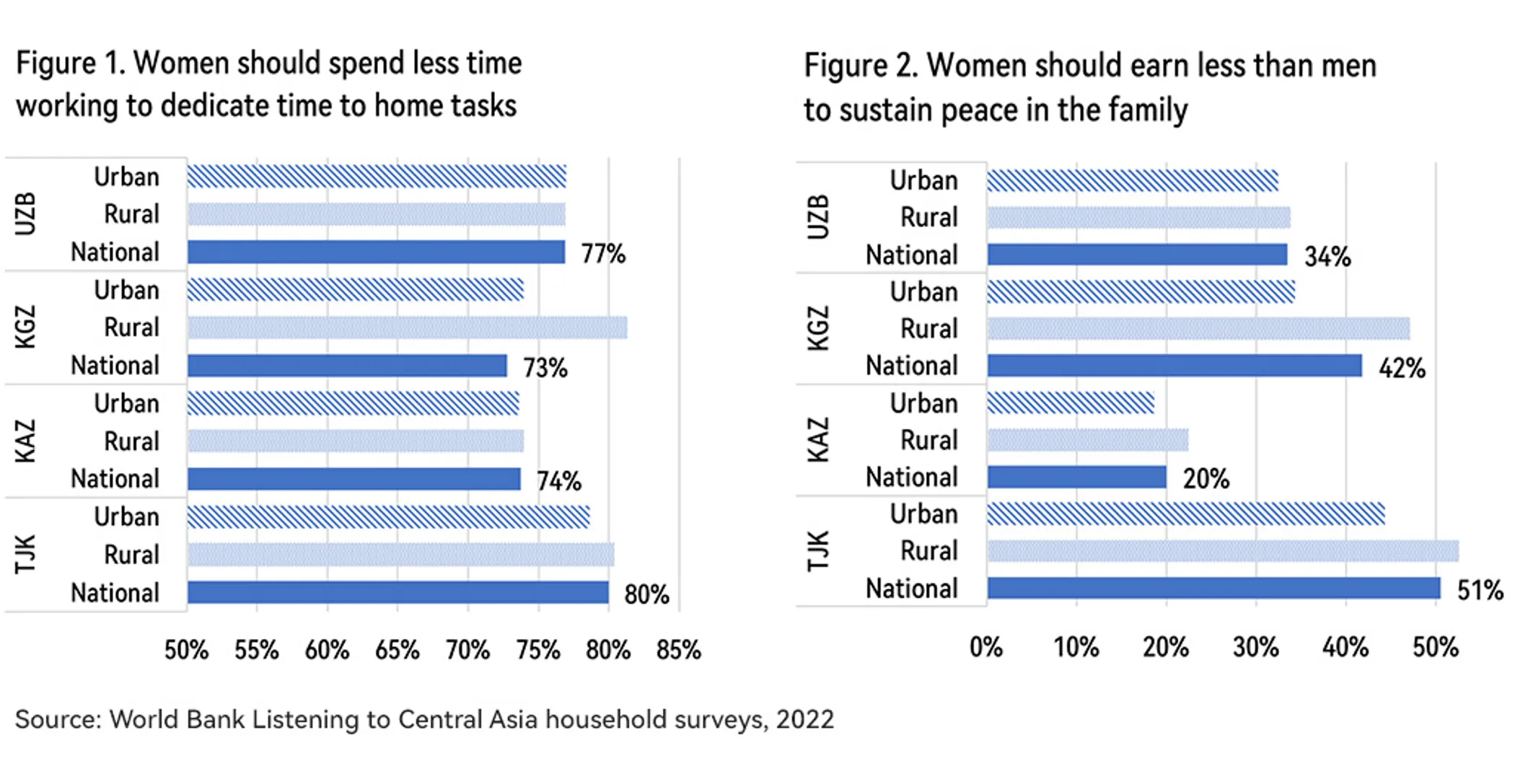

In 2022, two-thirds of respondents said that women should prioritize home responsibilities over their work, while men should be the primary breadwinners.

Between 20-50% also said that married women should earn less than their husbands for the sake of family harmony. And these patterns were relatively similar whether respondents lived in urban or rural areas.

Moreover, the researchers undertook two experiments that proved the existence of systematic bias against women in Central Asia.

The first experiment gave two groups of participants a short story describing the worker's professional activity and their salary. The text was the same for both groups. The only difference was that in one version the worker was a woman and the other a man.

Over 70,000 respondents were asked whether they thought the person described was underpaid, fairly paid, or overpaid. When the subject was a woman, respondents were 13% more likely to say she was overpaid. When the worker was a man, respondents were 34% more likely to say he was underpaid.

The second experiment addressed the inequality in hiring process. The researchers sent identical resumes of a fictional male and female worker to hundreds of real job advertisements in Uzbekistan.

The results were similar to the first experiment. For the position as a driver, the woman had to submit 180% more applications compared to the man with identical qualifications to receive a call from the job.