Disclaimer: This article contains sensitive content related to nuclear tests, such as description of the specimens at Medical Museum in Semey and may be triggering to some readers.

"I recall that we invited a lot of people from abroad – from the US, Japan, Germany," a man reminisces over a video call. “We took three buses to the Semipalatinsk Test Site. Icarus buses, I believe, and we drove right past the adjacent sovkhozes to the Site”. It was at the turn of the ‘90s when the Hungarian-made Icarus was seen in the Soviet Union as the pinnacle of bus amenities. The buses arrived at the gates of the nuclear facility, carrying an important group.

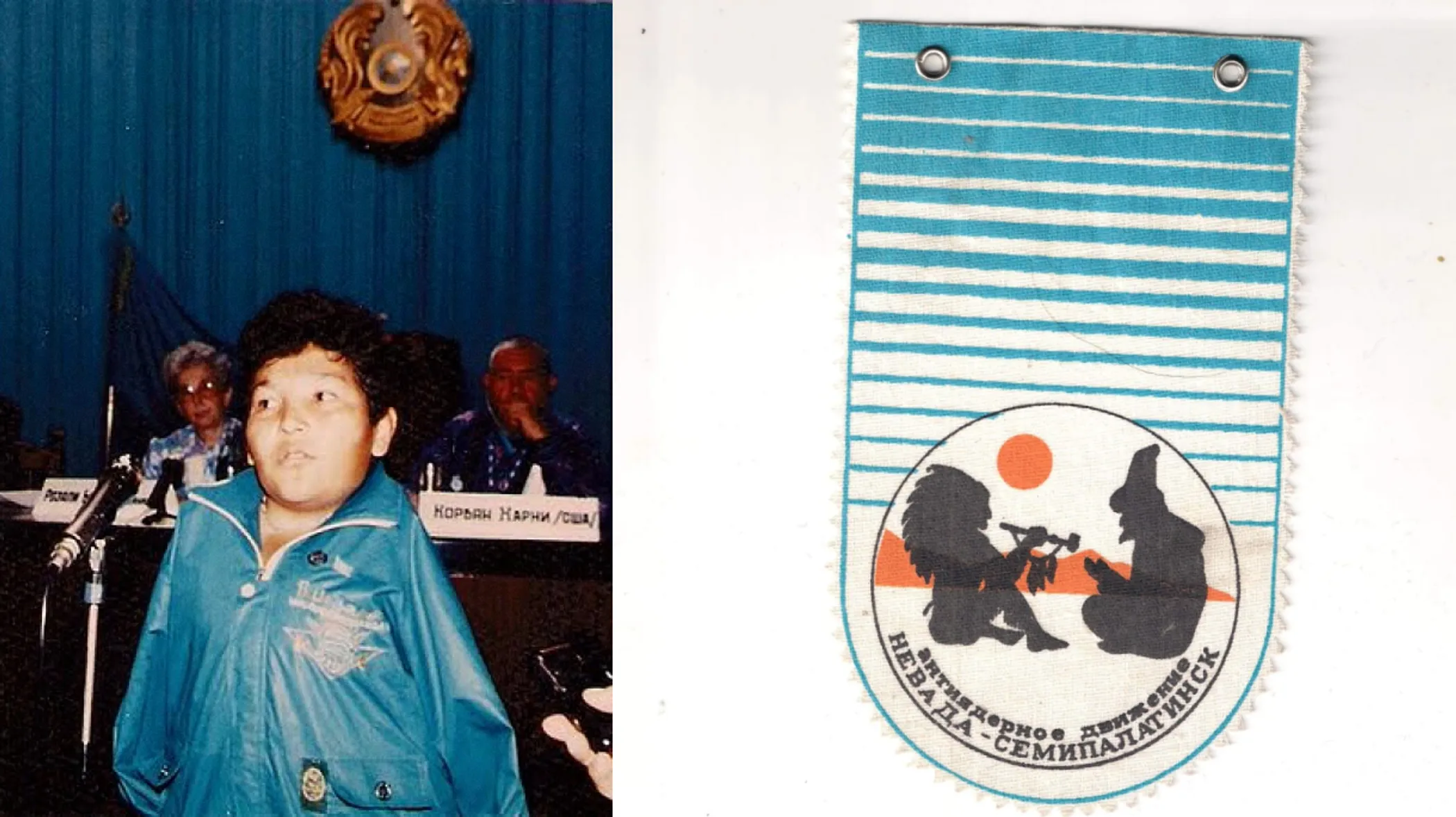

“We organized a rally there,” the man continues, describing how he and his group put up a peace pole in front of the soldiers guarding the entrance. A four-sided monument, each side bearing a message in one of four languages – Russian, Kazakh, English, and Japanese. “Then, as an act of protest — I had arm prosthetics at the time — I hung them up on the barbed wire, as a reproach to the military forces,” he recalled.

This man is Karipbek Kuyukov, an artist and an activist. While he has been a part of the Nevada–Semipalatinsk anti-nuclear movement since its inception in 1989, his connection to the cause began much earlier, in 1968. Karipbek was born without arms due to his family’s exposure to nuclear radiation.

During the interview with QazMonitor, Kuyukov couldn't recall the exact wording on the peace pole they made, but the first such monuments were erected in Japan in 1955. In consolation for those lost to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, they bear the phrase “May Peace Prevail On Earth”, coined by philosopher Masahisa Goi. It serves as a prayer for change, and the pole at the Test Site may have read something similar.

May Peace Prevail On Earth

Адамзатқа бүткіл дүниеде бейбітшілік болсын

世界人類が平和でありますように

Да будет мир человечеству во всём мире

The Semipalatinsk Test Site, located in Eastern Kazakhstan at the intersection of the Abay, Karagandy, and Pavlodar regions, lies 130 km west of the city of Semey. Covering 18,500 sq. km, it is a little more than half the size of Taiwan (36,197 sq. km), but its affected area is estimated at 304,000 sq. km, equivalent to the size of Malaysia (330,803 sq. km). If considered as a region, it would surpass the Aktobe region (300,629 sq. km) as the nation’s largest administrative body. Its grounds encompass the once-closed town of Kurchatov, the Site’s operational center, and several smaller settlements. From 1949 to 1991, these grounds saw around 468 tests — 125 conducted in the atmosphere and 343 underground. Today, satellite images of the affected area reveals craters left by the explosions.

Visible from low Earth orbit, these traces show the extent of the destructive power that was wielded at the Site. But, as Kuyukov notes, its scale wasn’t always so obvious. “In ‘89, there was a live Alma-Ata–Hiroshima teleconference,” he explains, “and the people from Japan thought they were the only country affected by nuclear weapons.” It was only after the Nevada–Semipalatinsk shed light on what was happening in Kazakhstan that it became public knowledge both within and outside the country. For Kuyukov it marked the first such event in his activist slash artist career. “During the broadcast, I drew a nuclear bomb broken in half, with a dove on one side and a Japanese crane sitting on the other. It was something of a poster for that teleconference,” and one of the earliest public visualizations of what has happened.

Since so much information was censored or simply hidden from the Soviet public, the Movement often had to act on the fly. Even its formation was spontaneous. “Our poet [and the movement’s founder], Olzhas Suleimenov, who was supposed to deliver a deputy election speech, said on a live broadcast that we're in a situation where we can't keep quiet about it anymore.” Suleimenov, says Karipbek, had a tip from the Site’s personnel that tests were presumably getting ‘out of control,’ and even the military started to worry about their children's health. “So, it was this collective rush, spurred by years of enduring and all the findings of just how much damage it did. People were set forward with the sole goal of shutting it down.”

You know, in Semey, there's a museum at the city's Medical University where they store these... wet specimens, embryos preserved in glass flasks. These were babies that were born. This 'Kunstkamera display', as I called it, has the two-headed ones, the one-eyed ones — they are all hair-raising. And there I stood, looking at them, facing the horror, thinking that I could have been one of them. That I was lucky. Then and there, I made a promise to spend the rest of my life as an artist, calling on people through my paintings.

Amidst the high-industrial landscape planned by the central authorities for Kazakhstan and its people, the Movement’s efforts carried a message of acknowledgment for the disadvantaged.

It must have been a sheer wonder to hear over the radio the signal that Sputnik 1 sent back to Earth as it became her first-ever artificial satellite on October 4, 1957. But its progressivist message was marred by the image of village families who didn’t know why is that the ground trembled and the sky rumbled near humanity’s first spaceport. Or, in Kuyukov’s personal experience, the power of nuclear fission was tainted by the stories he had to hear. “Sometimes, we would have to persuade them — the parents — to show their kids. They were cautious, of course,” he would recall. “These children were… doomed. They were never schooled; never received education.”

What will I do about it? I'm neither a doctor nor a scientist. All this just made me think about what I live for. That we somehow have to change this.

Between 1949 and 1962, a total of 111 tests were conducted, constituting the primary source of radiation exposure for the public. Those residing closest to the Test Site were exposed to fallout. The initial survey data became available at five-year intervals from 1949 onwards. Reports listed high incidences of all types of cancer, such as leukemia and brain tumors, which were reported in children living less than 200 km from the epicenter. According to the assessment by the government committee on June 24, 2005, the tests affected over 1.32 million people.

Even after decommissioning, the Site continued to pose a threat; the plutonium stored inside the facility was hazardous to both the environment and people. A secretive effort involving Kazakhstan, the US, and Russia began in 1996, selecting Degelen Mountain near the Site to secure the fissile material. In October 2012, several dozen nuclear scientists and engineers gathered on the hillside of the mountain to celebrate. The deed was done — the Plutonium Mountain had sealed the element with one of the highest atomic numbers to occur in nature.

The change Karipbek Kuyukov desired consistently took on international qualities. The Movement’s name, he points out, from the first day, was always 'Nevada–Semipalatinsk,' carrying the connection between communities near the Semipalatinsk Test Site and the Nevada Test Site.

“At the time, we were contacted by Western NGOs and were invited to the US by Greenpeace. I think we were there in '92, touring through, you could say, all the states and stopping in every city,” says Karipbek, adding that their ultimate goal was to set up a rally at the gates of the infamous nuclear facility. “With us, there were locals who lived near the Nevada Test Site. They were mostly Native American people — we even had a Shoshone chief beside us.” Thousands of kilometers from home, the members of the Movement found like-minded people wherever they traveled. "I remember a moment when I was speaking at a high school in Colorado," explains Karipbek, "I was addressing the students, and the next morning we had to travel to another city. In the morning, the students came and brought me two boxes." Inside was whatever they could find in the first aid kits at home – bandages, candy bars, even gum.

It was... I felt a sense of pride for the ordinary American people. The children. They made a choice for themselves.

As Kuyukov admits, it was and still is difficult to talk about the ways that the Test Site affected him. “I think back to the moment when we gave our first speech in Hiroshima, in 1990. We were there on August 6,” he says, recalling that the city was struck by a heat wave that day. The people were sitting on the ground to escape the heat. At the front of the Kazakh delegation stood Olzhas Suleimenov. He raised his hand, palm to the audience, and said that they traveled there to say to the Japanese people that they were not alone. The microphone then went to Karipbek. “I too am one of the victims of nuclear tests. I can't show you this gesture; I'll have to ask you to do it for me.” As soon as the interpreter translated his words, the entire square stood up, raising their hands. “And we stood on the rostrum, tears flowing from our eyes,” shares the activist. The people from the different corner of the planet understood his cause.

The Test Site that affected the hero of our interview and so many people across Kazakhstan was shut down nearly thirty-three years ago, on August 29, 1991. The Nevada–Semipalatinsk movement had protested every detonation conducted during the last three years of the facility's operation. Out of the eighteen tests planned, only seven were carried out.

Today, Karipbek is fifty-five, and he continues to treasure the image of the dove he drew so long ago. In 2021, standing before a vast canvas, a space meant to be adorned with a doodle of your choosing, he chose to draw a dove. “I believe that this is the common ground we share, this is what we need and what’s relevant,” says Karipbek. This was his contribution to the World Painting, an art project rooted in Kazakhstan, where each picture was drawn by one of the two thousand people, everyone who took the brush to its mosaic of world culture. Soon, shared Karipbek, that dove imagery will decorate collector coins issued by the National Bank of Kazakhstan.

“I consider myself fortunate to have had the opportunity to speak at the world's foremost podium, the UN General Assembly, where I addressed the heads of states that have not yet signed the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty,” says Karipbek. On the day of his speech, September 8, 2018, eight countries had not ratified or signed the agreement, but now that list grew by one more, as the authorities in Russia joined those in the US, China, Egypt, Iran, Israel, India, North Korea, and Pakistan. The connection all around falters, once again presenting the question, 'What will I do about it?’ Karipbek Kuyukov made up his mind a long time ago — his dove flies off old TV tapes somewhere in Japan, a painting that travels to art venues, and will appear on coins passed from person to person.