A hush murmurs for a second, as the moderator clicks away from a video – it was about reincarnation, told through Turkic mythology: a fly, a bird, and a snake, each belonging to different worlds. This is a screening. On the projected screen the mouse hovers over three works, a presentation, and some other files. Click. The studio goes dark, and the hush stills before an image.

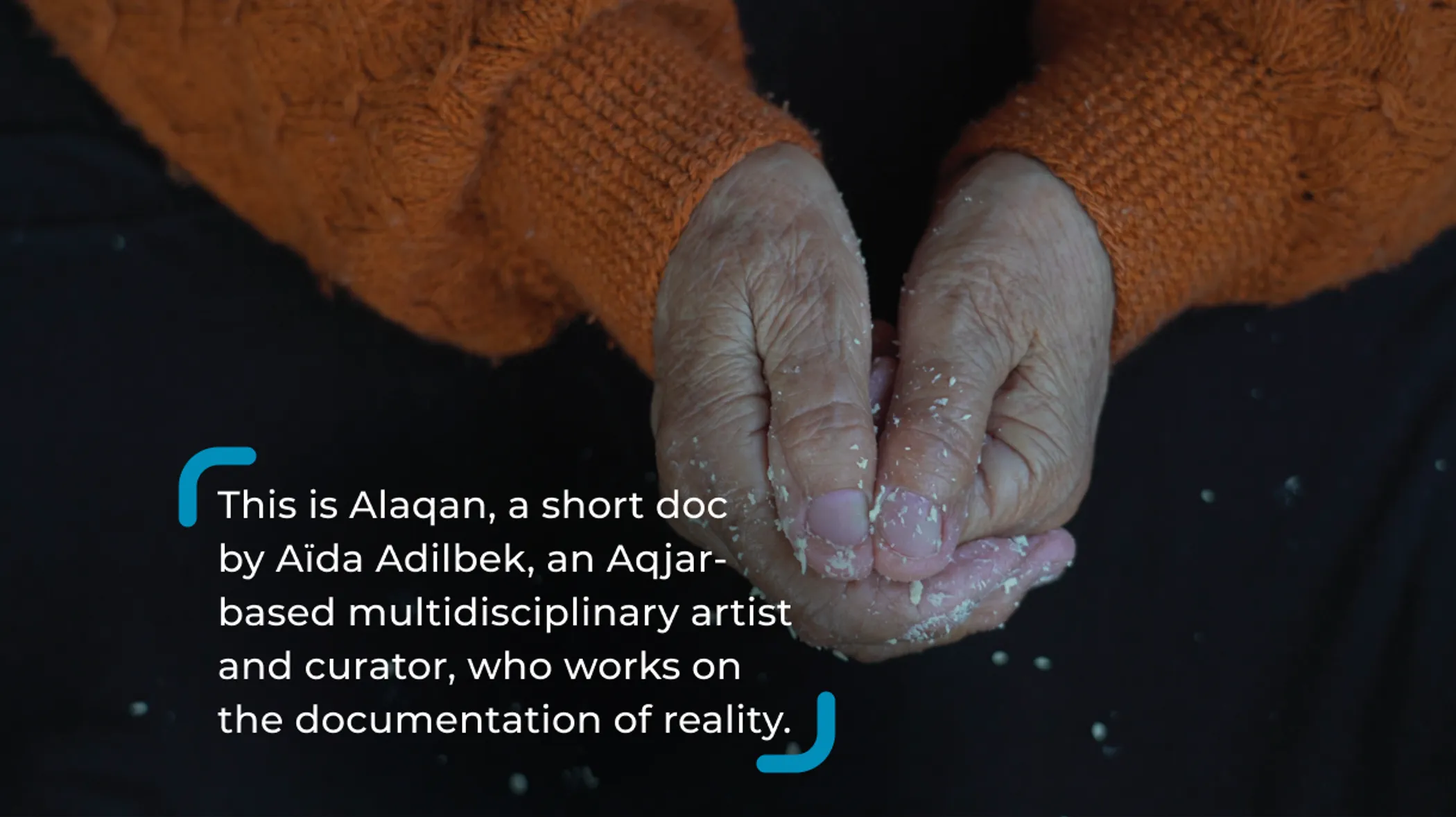

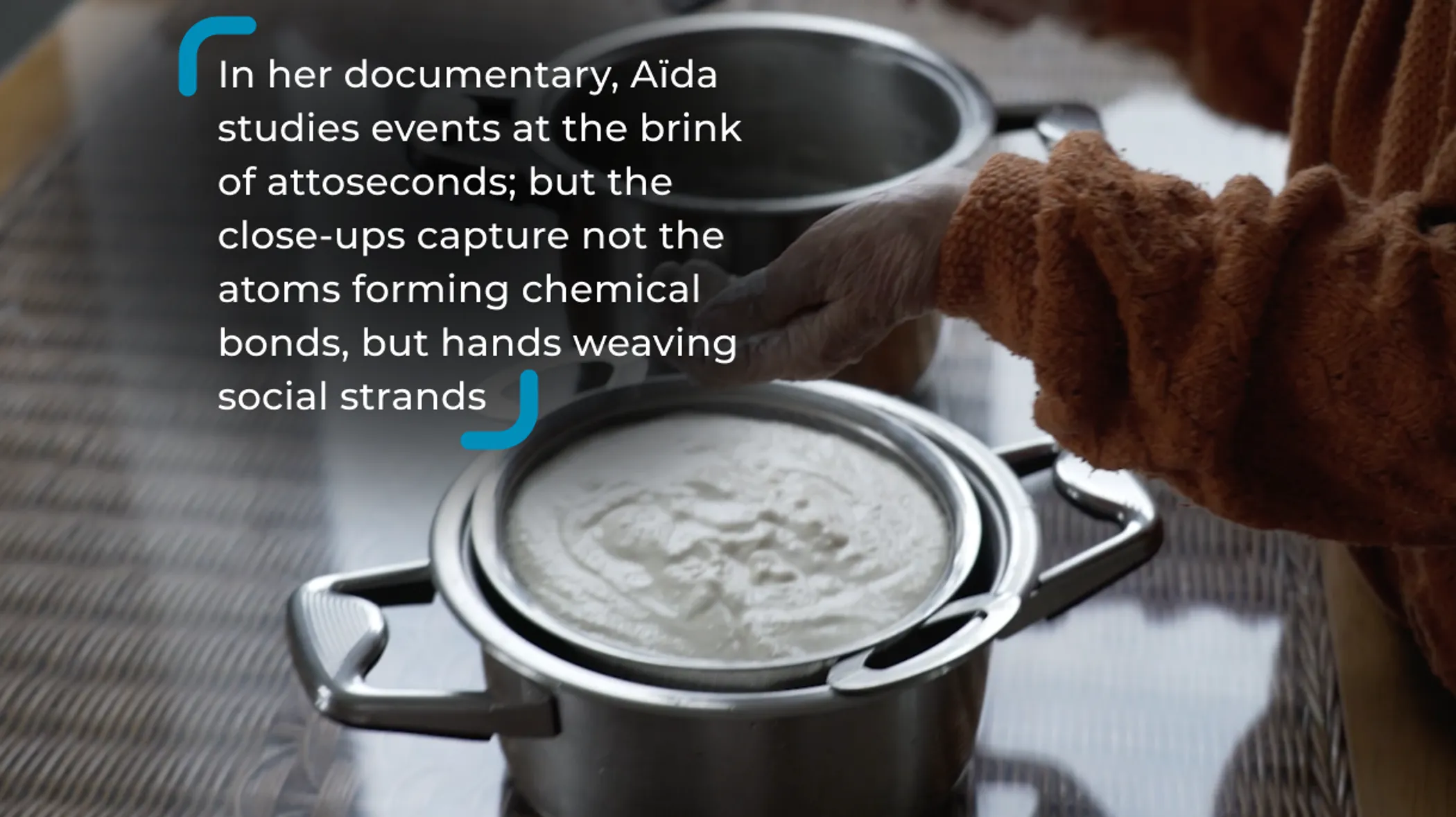

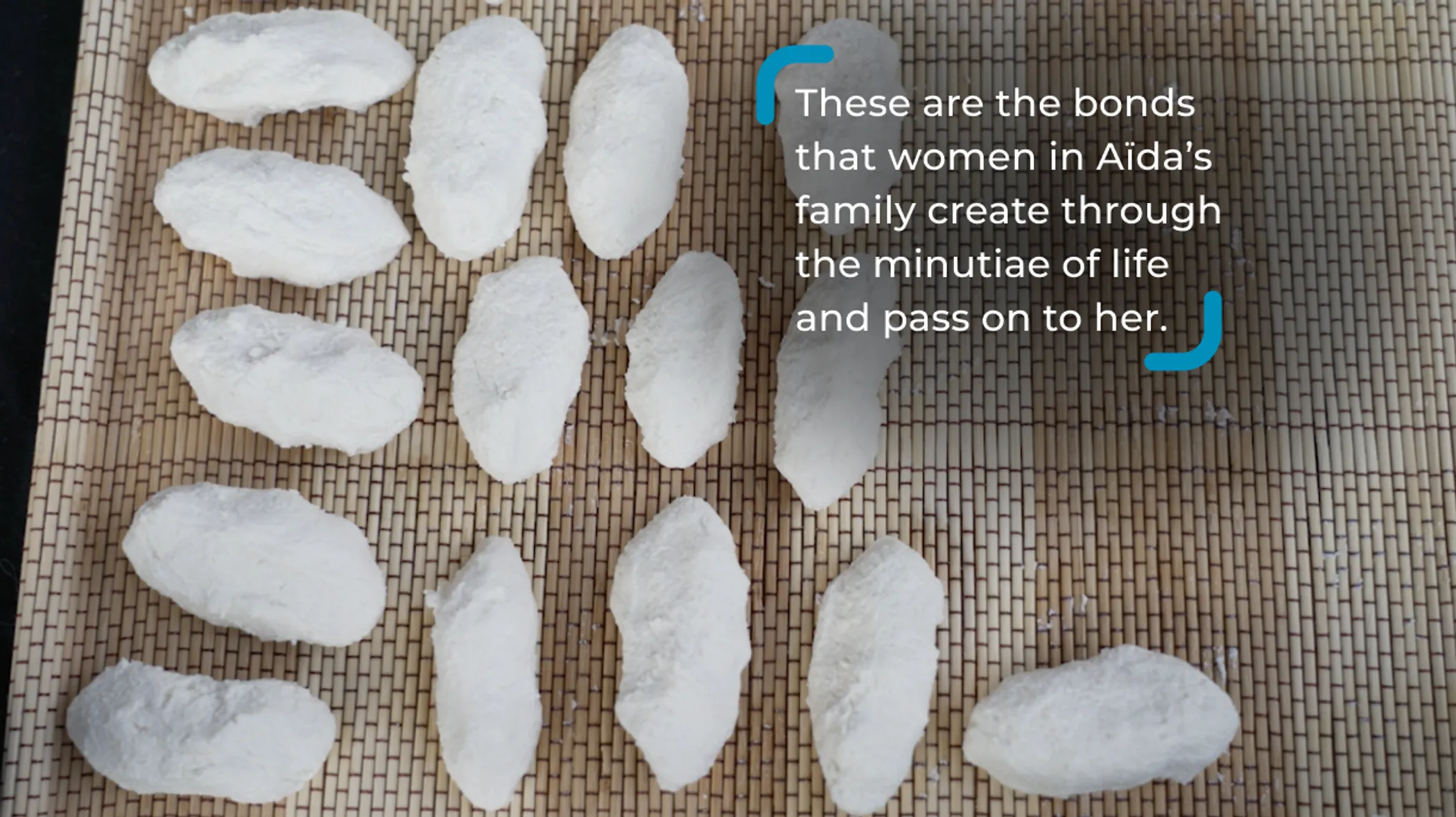

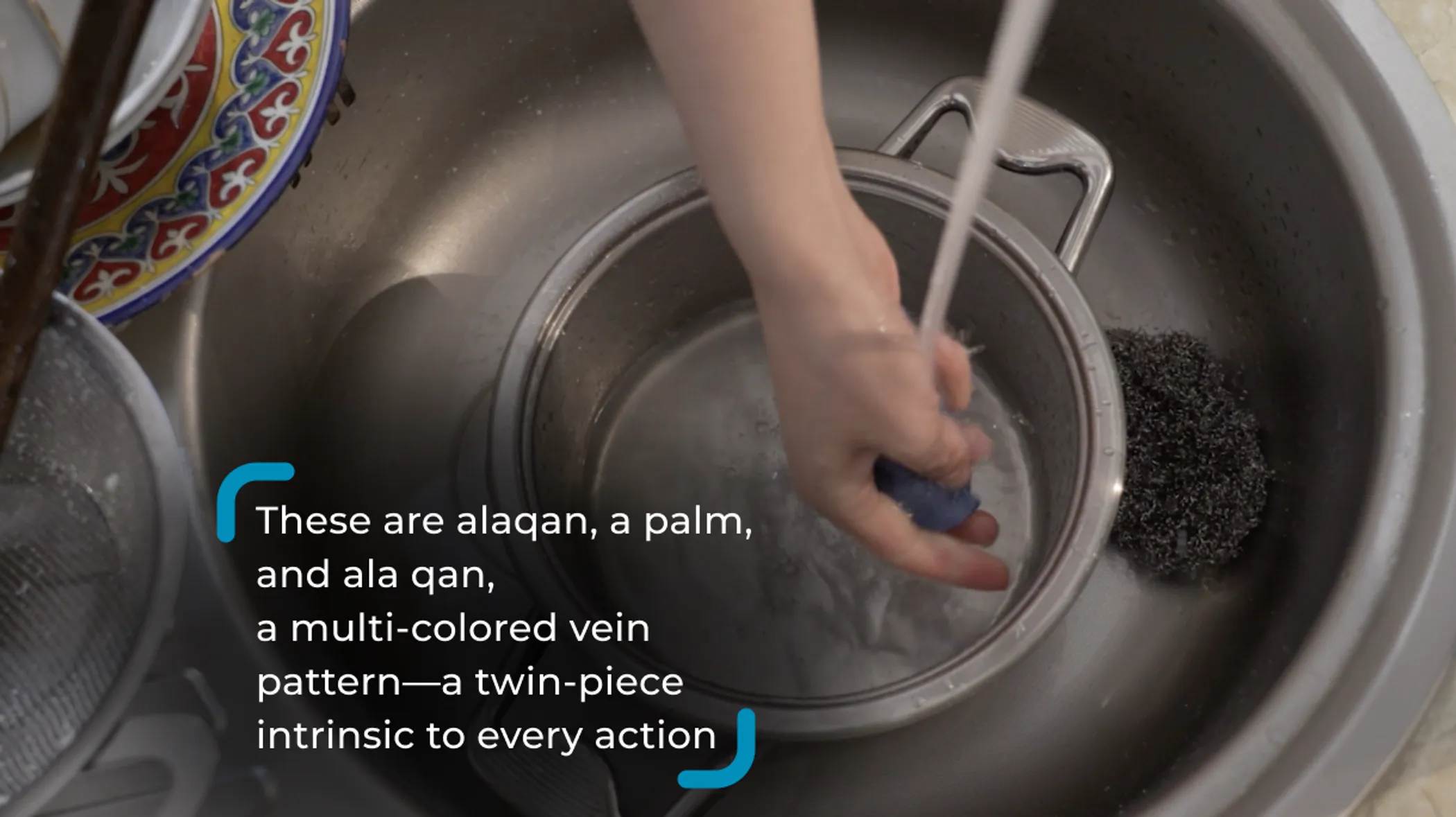

There are hands. Corporeal, palpable against a dark background, as if captured over a void. They appear submerged in the air, within a nothing space, tensed with stillness. The opening shot did its work, and we cut to a daylight-lit table, and a pot filled with milk. Today, we’ll learn how to make qûrt.

When Aïda hopped on a video call with QazMonitor, she said that, for her, "It was about that fundamental bond. To have it recorded, and reflected upon—the connections that I have in my family and how it makes me feel”.

What I’ve seen in my life and in my relationships with the women of my family is that most of the time, care and love go quietly, subtly. It’s just magic that goes around you and you take it for granted at some point. It can be very mundane and simple, but when you begin to wonder where it all came from, you realize that it has been crafted by someone's hands and, of course, by someone's love.

Aïda filmed Alaqan in 2022. That same year, the record of a woman preparing a traditional dish and her granddaughter following the process premiered during the DAVRA research group’s public program at the documenta fifteen, a contemporary art exhibition in Germany’s Kassel. Though it was filmed in Aqjar, a city district a few kilometers and subway hops from downtown Almaty, Alaqan can be easily imagined in some rural locale, crisscrossed by railroad tracks, with an imposing grain elevator looming for kilometers on end, but that wasn’t the case. “Alaqan was filmed at my house; it's my kitchen, my backyard. It was actually my grandma who visited. Every spring, she would come for my and my mom's birthdays, because we basically share it”, explained Aïda, adding that she also initially jumped on that bandwagon of authenticity, of how it was back in her childhood, drawing from memories of when her grandma would spend the night setting everything out.

But then I remembered—for the last twenty years, grandma lived in [the town of] Taldyqorǧan, in an apartment, where she made her qûrt in an ordinary kitchen. When we cook qûrt at home, it’s in this plain household, which looks very different from the stereotypical Kazakh imagery.

Unless you’re googling specific queries, the non-stock nature of Alaqan and how it would depict the local everyday life goes beyond preconceptions that are prevalent even within the ninth-largest country itself. That ‘vacuum-sealed bubble’, as Aïda calls it, is something that she, as an artist, tries to vacate sometimes, “to stay up to date and to know whether the questions I'm asking are genuinely important beyond my context and outside of my filter bubble”.

Many of Aïda’s interests stem from her home life in Aqjar, its intangible minutiae, and her exploration of the events that unravel unseen, only to be perceived through their effects. Even when she was occupied studying at Goldsmiths in south-east London, around 2018-2020, she would reconstruct a shared meal as a student project or have the video be the record for a practice familiar to everyone who had the (un)pleasure of living in post-Soviet apartments—banging on apartment radiators to quiet neighbors upstairs. In all of this, there’s a notion of locality, paired with Aïda’s Instagram bio saying, well, ‘freckled,’ but also that she is an Aqjar-based artist, both as an in-joke and a statement.

During those UK years, Aïda and her friends would have this powerful tag-phrase—‘Aïda Adilbek, a London-based artist’—all because some art curator at a venue casually labeled her exhibit as such, and, of course, what true friend could’ve possibly passed on this opportunity? Back then, “We had this running joke that it doesn't feel like I'm living in London or that I'm far away. In reality, I'm just hiding in Aqjar and not going anywhere,” recalls Aïda, continuing that, over time, this led her to rethink the relationship she has with her home city. Because Almaty is an expansive creature: a tourist crush for some, but clearly different for anyone actually inhabiting its bustling streets. “As an Almaty resident, born and raised, who lived all my life here, I grew up outside the downtown and have never lived in the Golden Square [QM — the city’s historic center], and for me—Almaty differs from that touristic image.”

So, I started to look at myself as a Qazaqstan-based artist, but the task of representing a whole nation is still much too difficult for me, and it would be this huge undertaking for the future. Likewise, I think, I am not representative of my city yet either; and, I’m more in my comfort zone being an Aqjar-based artist rather than an Almaty one.

That notion of the specific locality coexists with broader domestic art trends, and as Aïda explains, the local scene—and her work stands as proof of that—isn't heterogeneous, as artists explore various themes. “One of the biggest themes that many artists are asking themselves now is decoloniality, and how we reinterpret our culture, our history, our reality through that lens,” she says, adding that from her practice as an art curator, venues, both public and private, can and do go for decoloniality in their exhibits. But there’s a no-go zone, as “it's clear that state museums will likely be biased towards the agenda broadcasted by the authorities,” and political art will be severely underrepresented there. It may change though; right now, the southern metropolis is busy building the Almaty Museum of Arts and the Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture. Aïda is receptive but wary, saying, “Both, it looks like, signal that they are ready for experiments. So, we'll find out when they're commissioned how open they are”.

Contemporary art, art in general, plucks the nation’s strings, and right now there’s a nice rhythm ‘n’ pulse to it, but the way Aïda sees it, it doesn’t reach enough ears. The lack of public broadcasts has city crowds rely on word of mouth or small niche media, hurting the numbers seen at the venues. So, when Aïda is deep in her conceptual work, she has this on the back burner, “there is this private, reclusive part of it that is mine, and there is the part when we open up, give everything to people, and everything should be accessible,” she explains.

In 2020, right after graduating, Aïda and her alumnae friends founded MATA, an artist collective. Since then, they’ve been stirring the place, racking up some community rep amid the media quiet.

As Aïda admits, the manifest goes hard in opposing elitism and nepotism narratives in the artistic milieu. Written right after the Covid lockdown, it carries itself with a stored-up idealism and seeks to confront gatekeeping all across the community, but…

It has an attitude that just wants a stand-off. As I got a little older, I realized that there's more to art than that. It’s not just about confronting evil; it’s also about coming together, opening up, and being flexible. That's probably what's been missing for so long [in the art community].

Three years have passed since, and MATA has had numerous meetups – lectures, workshops, and whatnot. "We periodically organize reviews,” says Aïda, weighing this practice to the idea of competition in the capitalist society. “Instead of hiding what you do and keeping it hush-hush until the end, it's the opposite,” she says. “This way, we can look at each other's work in a cozy and open atmosphere, find out who is doing what, and understand what is on our minds."

This March, Aïda has a project coming up in Paris, a sort of finale to a year-long Sound Art residency at the Musée du Quai Branly, so, the year kicks off busy. “We are going to work with the notion of grief and loss. I want to think about death not as a finality, but more as a transformation—when we come into this world, and when we move on,” shares Aïda, pointing out that this work will draw from her residency in France. Selected as a participant in 2023, she had access to the museum’s vast collection. There, artists from all over were presented with a historic link—be it musical or textile artifacts—to reconceptualize their cultures through age-long sound practices.

The project’s name comes from Abaï's poetry, 'Öleñmen jer qoïnyna kirer deneñ.' I believe this phrase captures not only the culture of people from Central Asia but also the entire world. Chants and oral tradition can be found all over, and this phrase literally translates to 'Your body shall return to the earth with a song.' If you look at our culture, we have bata (blessings), prayers, and songs. A toolkit of sorts for any event in a person's life, from birth to their death.

“I have a keen interest in folklore and reimagining its characters,” says Aïda, sharing ideas she has for this year. Jeztyrnaq is the name on her mind. In fairytales, Jeztyrnaq is a blood-hungry spirit who hides her elongated copper nails behind the long sleeves of her dress, but for Aïda, she is a guest from her childhood memories and has piqued her interest more than once. “We often see that the antagonists in Turkic mythology are female characters,” she muses, adding that this project has been in the works on and off since 2018, but this time, Aïda’s trademark exploration of that which could not be observed may delve even deeper still.

NOTE: This interview uses the Latin alphabet for Kazakh proposed by MATA.