Kazakhstan is witnessing the emergence of a vibrant new generation of local writers. Today, works of domestic authors grace the shelves of bookstores, encompassing not only historical volumes but also novels of young talents.

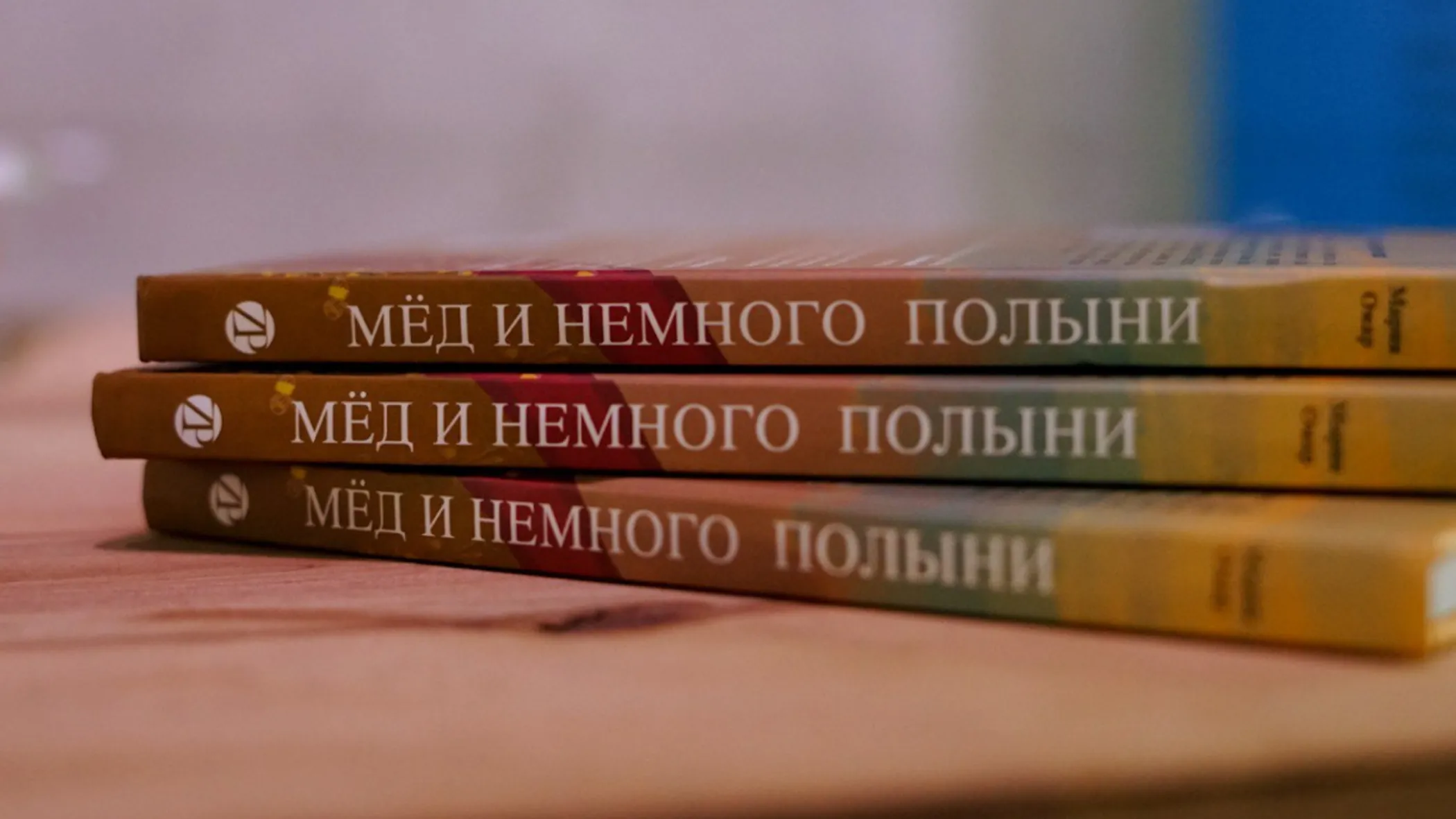

Among the rising literary talents is Maria Omar. Her book, titled ‘Honey and a Hint of Sagebrush’ [‘Мед и немного полыни’], delves into themes of famine, war, the turbulent 90s, personal struggles and joys, all through the eyes of three generations of women. The narrative is inspired by the lives of her grandmother, mother, and her own personal journey.

In an exclusive interview with QazMonitor, Maria Omar shares her journey to becoming a writer, discusses challenges faced by women in different eras, and sheds light on the way Kazakh traditions were preserved in her own family while living in Russia.

When and how did you decide to become a writer?

Since childhood, I always carried a notebook and a pen to write down stories. I would ask my family and guests who came to our house for their names, their parents' names, and their family tribe - ‘ru’, and compile genealogies.

Throughout my school and university days, I dabbled in creating parodies of well-known poems and songs for various occasions. I was actually studying to become a biology and geography teacher, but unexpectedly for everyone, I became a journalist. It was a coincidence, although perhaps not. My brother met an acquaintance who had started working as a journalist and told me, "This suits you, give it a try!" I wrote an article and later got a job in a newspaper in Orenburg, where I honed my writing skills. However, it was in a journalistic style. I only started learning to write in a more artistic language in the last few years.

I constantly write, even when I'm sick or when I was in the maternity ward. While I am writing, I forget about everything else. So, perhaps it is some kind of predisposition of mine.

Tell us the story of creating your book ‘Honey and a Hint of Sagebrush.’ What themes and ideas inspired you to write this book, and why were they so appealing to you?

My book is based on real events, although there are some elements of fiction.

The inspiration for this book came from the story of my maternal grandmother, Akbalzhan azhe, who became the prototype of the main character in the book. I was always fascinated by the tales of her extraordinary life. Some facts from her biography are hard to believe, like how she left her husband in the pre-war year of 1939 with two young children. Such occurrences were very rare.

She not only survived but also experienced love and passed on her love for her homeland to her descendants, even though we were raised in Russia. I wanted to tell the story of a woman who, despite the challenging times, managed to assert her right to happiness. I wanted to show how historical events such as famine, war, and restructuring influenced ordinary people and how they coped with it. I was interested in tracing how one's choices during difficult times not only affect their destiny but also the lives of future generations.

Your book tells the story of three generations of women in Kazakhstan. What are your thoughts on the challenges faced by past generations of women? Which of these challenges have changed over time, and which remain unresolved?

Certainly, the women of the pre-war period had a much harder time maintaining their dignity and freedom, given that it was a matter of physical survival. People endured so much suffering that they had to suppress their emotions, "harden" themselves to avoid breaking down from pain, otherwise, they might have gone insane. This is why many women of that time were very strong, tough, and displayed little warmth toward their children, substituting it with care. My grandmother's saying “Basy aman bolsyn” - "The main thing is for everyone to be alive and well," profoundly echoes the sentiments of that time. It was essential to stay alive and raise children, to continue one's lineage.

Nowadays, women live in more prosperous conditions and have the freedom to choose how they want to live, especially in large cities. However, many problems have persisted. Instances wherein women, especially those with children, find themselves dependent on their husbands and in-laws, devoid of a voice, and subject to societal condemnation and stigmatization when raising children alone still plague our society.

I have had conversations with numerous women who have endured physical and psychological abuse within their families, and unfortunately, women often find themselves defenseless in such circumstances, even though there are organizations in the country trying to help them.

What part of creating 'Honey and a Hint of Sagebrush' was the most challenging for you?

The most challenging part was writing about myself. The stories of my grandmother and mother had already taken shape, and I knew which events needed to be described. As for the third part, where I write about myself, I had doubts about how interesting this topic would be to readers who were unfamiliar with me. As a result, I left out the chapters about my teenage years. First, they didn't fit well into the book's overall structure, and secondly, I found it hard to be candid. After all, there are plenty of personal experiences that are difficult to share with others. There were moments of self-censorship, especially in describing some stories because I hardly changed the names of the characters. What if someone gets offended, or there is a misunderstanding? So, I had to remove some parts even though they could embellish the work from an artistic point of view.

Your book frequently mentions Kazakh customs and traditions. How did your family preserve and pass on these national traditions while living in Russia?

I lived in a village in the Orenburg region where the majority of the population was Kazakh. In my childhood, there were many Kazakh grandmothers dressed in traditional attire: ‘kazhekey’ [traditional vest] and scarves, making ‘kurt’ [dried salty cheese] and ‘zhent’ [dessert made from wheat groats and dried cottage cheese], speaking Kazakh, and being well-versed in customs. Over time, of course, part of the population became more subject to Russian influence.

Nowadays, very few young people in that area speak Kazakh, but there is still a generation from the 1940s and 1950s, and many customs have been preserved: ‘sogym’ [stocking away meat for winter], ‘sadaka’ [voluntary charity], ‘betashar’ [the ceremony of opening bride's face], and others.

I do not know what the future holds. Much depends on the family. There are Kazakh families where grandchildren call their grandmother ‘babulya’ in Russian. Kazakh traditions have been preserved in our family thanks to my grandmother and my mother, as well as my father, who not only did not object to it but supported it. My father’s grandchildren even call him ‘Ata’ despite the fact that he is ethnically Belarusian.

I really liked the descriptions you used in the book; while reading, you can feel the aroma of baursaks, freshly brewed tea, and salted kurt. What helped you paint such an authentic picture of Kazakh life?

What helped me was the fact that I lived in that kind of environment and saw most of what I described with my own eyes. If we are talking about the earlier years of the last century, my mother's memories helped me a lot. She is very attentive to details and described them to me meticulously. She told me how children used to exchange old items for whistles with the old peddler, how women sewed bags from discarded parachutes, how they used traditional methods for healing, and other things that would be challenging to invent or find in archives.

What do you think about the current state of the book [publishing] industry in Kazakhstan?

The book industry in Kazakhstan is not as developed as in European countries. There are still relatively few books in the Kazakh language, although the situation is much better than it was 15 years ago. I remember going to the largest bookstore in Aktobe to buy a book in Kazakh as a gift, and not finding any. At that time, I wrote an article about it. Nowadays, there is a fairly extensive selection of children's literature in Kazakh, which is a positive development. However, when it comes to books in other genres written by local authors, there are still very few, judging by the shelves in bookstores.

How was your experience publishing your book in Kazakhstan?

When I wrote my book, I had a very limited choice of publishers. I was often told that publishing a book in Kazakhstan is only possible at your own expense. Many authors target Russia, where the publishing market is broader, or they resort to self-publishing. I dreamed of publishing my book in Kazakhstan and, preferably, through a publishing house. I will not hide the fact that there were a few rejections because publishing houses are often reluctant to engage with unknown authors, which presents a risk for them. Eventually, I found a publishing house interested in new voices, and my book was published by Zerde Publishing, a young Kazakh publishing company.

How are literary communities developing in our country?

This year, I discovered the USW writers' club, organized by Andrey Orlov. It is a fairly active community that includes both experienced and aspiring writers. We hold meetings, presentations, training sessions, and festivals together. The community is soon releasing a collection of works by local writers. We support one another, communicate, provide advice, collaborate, and this is very beneficial for all of us.

Additionally, in our city, there is the Open Literary School of Almaty, where training, events, and competitions are organized.

There are several book clubs where you can exchange opinions on books you've read. For example, I was recently invited to a meeting at Adebi Club in Astana, where young people gather. It's fascinating to observe such clubs, as there is much to learn from them, such as how they popularize reading on social media.

In your opinion, what programs or initiatives could contribute to the development of literary culture in Kazakhstan?

It would be great to have more support for literary projects. Currently, festivals are often funded by writers themselves or through sponsorships found by organizers. We need more educational programs, grants for writers, residencies where we can exchange experiences with local and international colleagues. Most of our learning is done online, often at our own expense.

Literary awards often come with age or genre restrictions, although some like the "Qalamdas" award have recently removed many of these limitations, which is encouraging. However, there are still too few such awards.

It would be wonderful if Kazakhstan had a convenient and accessible electronic platform where authors could upload and sell their books. A significant step forward would also be the creation of a hub, a space where writers, those interested in our work, and representatives of organizations we could collaborate with could come together.