Kazakh comic book artist Magira Tleuberdina has been passionate about drawing since the times when she was too young to even speak. Her artistic journey began with the shapes and angles of beloved Nickelodeon and Disney cartoon characters. Those Saturday-morning cartoons paid off, as Magira is now transporting that vast realm of nomadic mythology within inky panels of her works.

Still nascent in Kazakhstan, the industry here is in need of unique voices, and that’s where Magira delivers. Her Qabanbay and Mergen defy stereotypes surrounding legendary warriors of the Great Steppe — Batyrs, historic figures, whose cultural influence in Kazakhstan is akin to Western knights or Eastern samurai.

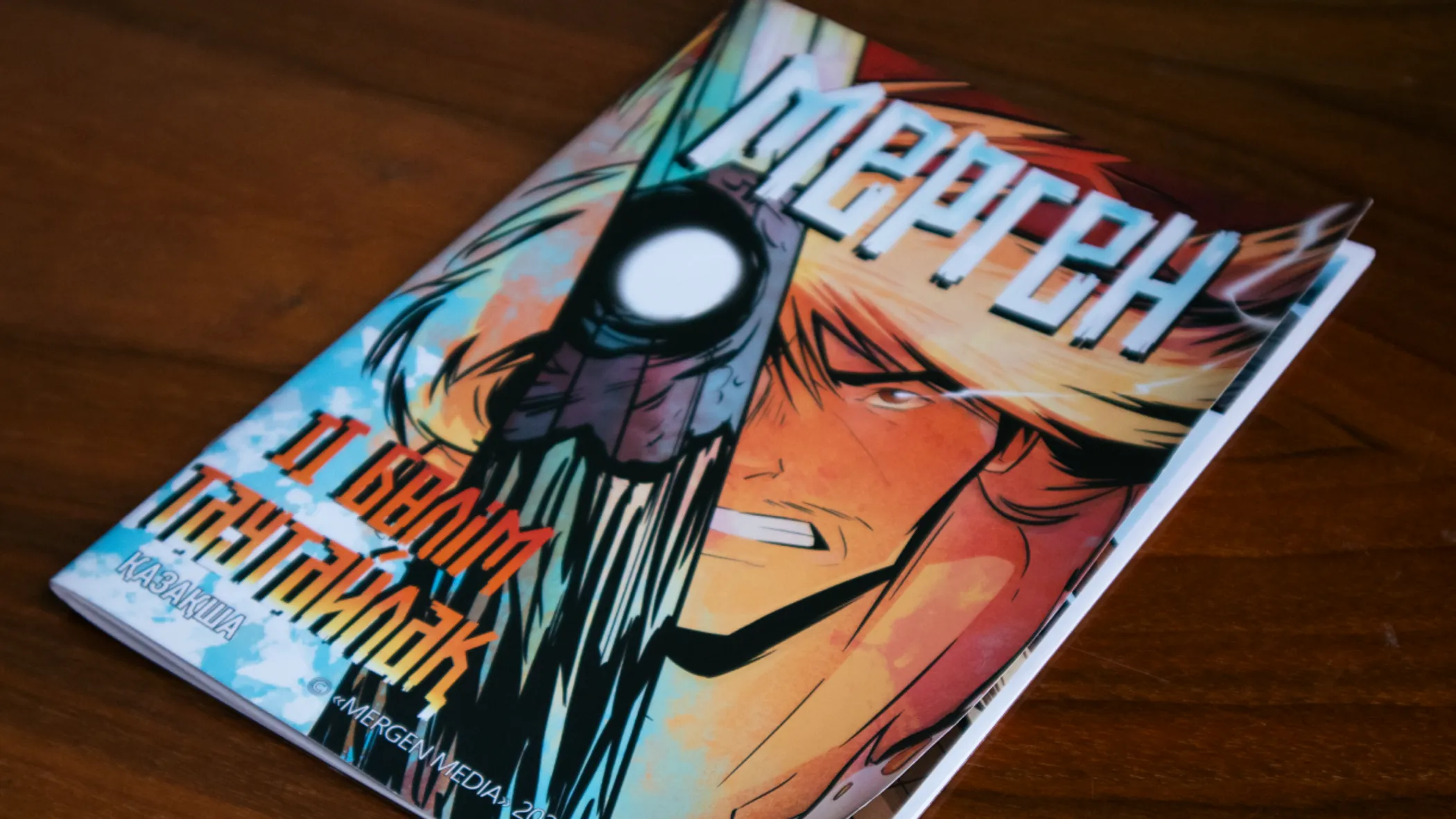

Magira recently released the second issue of Mergen, and now the artist is exploring the dark fantasy realm of Kazakh folklore and putting her hero against supernatural entities and eerie spirits with stories shaded in hues of horror.

QazMonitor reached out to Magira to ask about challenges and aspirations of the Kazakh comics industry, and how comic books can become the foundation for local animation pictures and movies.

Untapped setting

Recently, you released the second issue of your comic series, Mergen. How does your first comic, Qabanbay, differ from it?

I began working on Qabanbay driven by my emotions, filled with excitement as I delved into new tasks. Somehow it evolved into a humorous comic. Very cartoonish and light-hearted – goofy, but sincere.

But when I started selling it, people would have this strange aftertaste. Because everyone expects that if it's a comic about Qabanbay, then he'll be this brave and masculine hero, being all about brawls and battles. In my comic, Qabanbay was an ordinary teenager who had his fears, was quite shy, and—unexpectedly, even for himself—managed to defeat a boar [qaban is Kazakh for boar – QM].

Then, while I was contemplating the sequel, I received an offer [for Mergen comic book]. The project was on the table, and all it needed was an artist who could bring the story to life. I agreed, thinking to myself, "I have nothing to lose; I'll try my hand at a more masculine comic book."

What interests you about Mergen?

If in Qabanbay I had to work with only twenty pages, Mergen would expand [my workload] to thirty pages. It's an intricate story with various monsters making appearances, demanding dynamic fight scenes. I had to familiarize myself with the fundamentals of drawing, such as anatomy and perspective.

While working on Mergen, I realized that I had developed a genuine affection for this story and its main character. But, we had this disagreement with the writer about Mergen's characterization, his experiences, his inner world—what truly defines him. We couldn't find a common ground and I ended up working on Mergen alone, taking on both the roles of writer and artist.

I wanted him to be this down-to-earth type, and to get rid of all these stereotypes and clichés about batyrs – that they were some kind of immortal heroes, who were like machines that would just follow orders or something. Because, in truth, it was quite different.

Each region had its legendary warriors. We – nomads, Kazakhs – had a widespread institution of batyrs. Yet the topic remains largely untapped; no one has really portrayed it yet, but it's just such a vast setting.

The time to draw has come

What can you say about Kazakhstan’s comic book industry? How well-established is it?

Well, our industry is not developed at all. We have Khan Comics, which has already transitioned to making cartoons, and they are currently the only publisher that both prints, publishes, and supports authors. I also know that we have a studio called Tasqyn. They are a group of artists who banded together in one big team and decided to create animated series and comics.

I thought that I would collaborate with [Khan Comics] on Qabanbay’s sequel, but I'm a little bit scared of this whole system of publishing houses. We lack a developed community – where one supports another – even with donations, not to mention the fact that our comics are few and far between, and they don't often break even.

Speaking of community, what kind of difficulties do comic book artists face in our country?

One big problem is that we have a small population, many people aren’t aware of this industry yet. Though, based on the latest festivals, where I participated as an artist to gauge interest in my comics, it was mostly young parents who were buying comic books for their kids. So, one of the difficulties is the financial aspect because it is challenging to break even, but it just requires time.

Secondly, you absolutely must patent all your work. This can be done very easily; for example, if I post my drawing on social media and sign it, it already provides a kind of protection. If you are an artist, you should definitely try to publish your work, document it, keep the source materials, so that there shouldn't be any problems.

I’d like to add that it takes time for our people to get used to a subjective, artistic point of view. For example, I studied in a typical local school, where it was customary to write essays following strict guidelines. All works looked exactly the same, when someone got things 'wrong', we were poised to criticize it. But it's possible to present [stories] in completely different ways. For instance, the story of Queen Tomyris can be a musical, a comedy, a drama, or even as a horror story. I think these boundaries should be erased.

Lastly, I don't see many of our comics on our shelves. But there is hope as different independent authors and artists who want to bring their ideas to life are emerging.

Let's hope that everything is still possible. As much as we would like to, for example, jump straight to cartoons, comics are primarily about good scripts – ready-made scripts for animation, basically. It's a necessary step that we need to take to develop our movie and cartoon industry. So, it’s high time you draw comics.

QazMonitor team thanks Photobar Studio in Astana for providing their venue for the photoshoot.