Astrophysicists from Kazakhstan participated in NASA’s space mission to test whether humankind could change an asteroid trajectory to prevent it from crashing into Earth, QazMonitor reports with reference to Tengrinews.

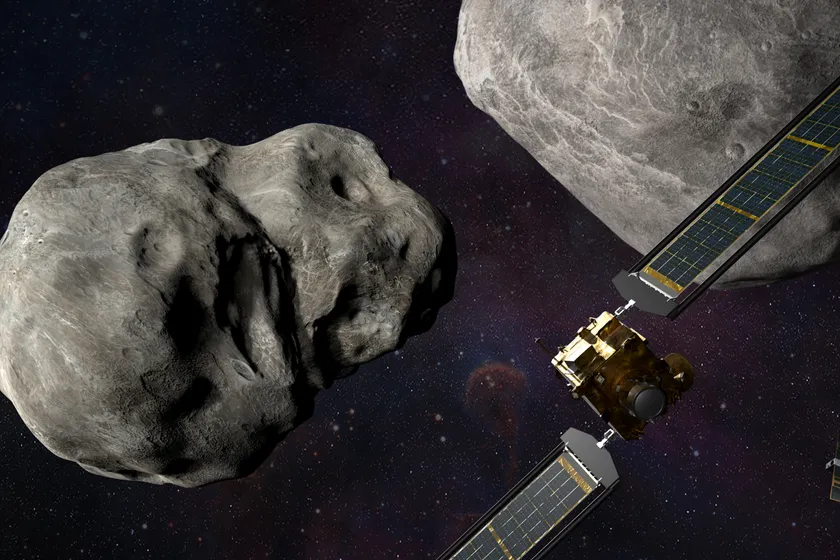

Almost a month ago, the DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) spacecraft crashed into the asteroid Dimorphus, successfully altering the space rock’s orbit. “This mission shows that NASA is trying to be ready for whatever the universe throws at us,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said during a briefing at NASA headquarters in Washington.

Astronomers from around the world watched the mission, compiling various reports and papers on the potential effects of the crash. Among them are scientists at the Fesenkov Astrophysical Institute in Almaty.

Alexander Serebryanski, the head of the Observational Astrophysics Department, who gave an interview to Tengrinews, shared that the Institute created an international collaboration to participate in the NASA project.

"As a rule, astrophysicists initiate observation campaigns for large space projects. My foreign colleagues and I created a group, which included scientists from Finland, Russia, Italy, and Uzbekistan.”

Serebryanski said the task of Kazakh astrophysicists was to observe the event before, during and after the impact using a spectrograph and a new telescope they built themselves. The telescope is installed in the Assy-Turgen Observatory located near Almaty.

The DART mission was observed by scientists from different parts of the Earth.

“But we filmed the very moment of the impact and did a spectral analysis at the same time. Scientists from other countries were simultaneously observing how the overall luminosity of the asteroid was changing. Others were observing how the polymerization changed to find out what part of the material was dust.”

The telescope built by Kazakh scientists proved to be efficient in gathering high-quality data despite the unfavorable weather conditions during the time of the impact. Using the data, Serebryanski and his colleagues are preparing research papers and articles that will be published in leading scientific journals around the world.

"The analysis is done and the international campaign prepares the work that will determine the total mass and what was thrown into space more: gas or dust. Everyone is doing their own part and preparing material for publication in an international publication."

This is the second time Kazakh scientists are involved in a large-scale international project. The first was a project on another potentially hazardous, near-Earth asteroid Apophis, which is estimated to come as close as the distance of the geostationary satellites in 2029.

Currently, the astrophysicists are preparing for a third observation campaign, this time, on the asteroid Phaeton. "Each asteroid is assigned a specific task. For Phaeton, the Japanese mission was tasked to land there. We will make observations for them, and their results are of great interest to this team," Serebryansky concluded.

Over the past few decades, scientists around the world have been actively monitoring near-Earth asteroids and conducting a kind of cosmic census to understand how dangerous they are to humanity. Because of the sheer number of asteroids, astronomers had to create special scales to estimate how likely they are to crash into Earth.