Kazakh comic books and animation. Just a couple of years ago, this phrase was reserved solely for media archaeologists who delved into its history. Take the first Kazakh animation, Why the Swallow Has the Tail with Little Horns? (Қарлығаштың құйрығы неге айыр?, dir. Amen Khaydarov), for example. Released back in 1967, it just a year later bagged an award from the Third All-Union Film Festival in Leningrad. There was a whole story behind it, as the animation staff were all self-taught artists who banded together to bring the popular fairy tale to the screen. Nowadays, that tale and other old cartoons seem a bit unusual and don’t fully meet modern expectations of what a cartoon should or can be.

One of our speakers, comic book creator Magira Tleuberdina, once told QazMonitor that drawn stories and animation are so interconnected that one can't exist without the other. Comics are "ready-made scripts for animation," and "It's a necessary step that we need to take to develop our movie and cartoon industry."

Today, we’ll take a look at what the current generation of Kazakh comic book creators has to offer and the small steps that the animation studios here take into the great unknown.

It’s the first day for fifth-grader Saniya at her new school. She has already found her new love for life, Zhasik, whose desk conveniently sits parallel to hers, and everything is lining up to be perfect, but… Alibek Kozhageldiyev didn’t take visual cues from O'Malley’s Scott Pilgrim for nothing; that highly kinetic action merely lies dormant, waiting for the story to kick off.

This is We Are Not Superheroes (Мы не супергерои), a graphic novel about Saniya and Zhasik, as they accidentally — as in ‘Joker falls into acid’ accidentally—gain superpowers. Turns out, it’s not really a boon, as many people would like to get a hold of their power. But Alibek’s creation is never without wit, and its two-perspectives-same-scene approach pays off as it enriches and gives character to the heroes as they navigate obstacles differently.

Where to find: Suitable for readers aged twelve and up, We Are Not Superheroes is a black-and-white 130-page light-read. The comic book is available in Russian.

It's dark and scary outside, and well past their bedtime, but three puppies—the eldest, Tima, and his sisters, the swift-tongued Lala, and the smarty-pants Sulu—are swapping spooky tales under the blanket. Who will go to sleep soundly this night, and who will reveal themselves as the scaredy-cat of the bunch?

Our next entry is the all-ages adventure of Kunshikter (Күншіктер), a bite-sized cartoon about three puppies who adore fun and enjoy a bit of mischief to balance things out. Produced by Tasqyn Studio, Kunshikter alongside Bes Tai Tai (Бес тәй-тәй), marks their venture into children’s animation, and they executed it masterfully. Each episode follows Tima, Lala, and Sulu as they go up to a new obstacle in their day-to-day, be it a new facet of emotion or an activity they're unsure how to tackle.

Personally, when it comes to Kunshikter, we are on a lore hunt of sorts because Tima and Lala are green and orange, just like their dad and mom, but Sulu is the outlier here; she is blue. In episode seven, the pups were supposed to have their aunty Aliya over, but the episode’s premise resolved so fast that we never saw what she looked like. Now, the burning question – does Sulu take blue from her mom’s or dad’s side, is aunty Aliya blue? There are clues left by the animators hinting at a bigger picture that exists beyond the on-screen storyline. With how scarce the world of Kazakh animation is, a cohesive setting is a rarity, yet Tasqyn Studio managed to capture that elusive beast of environmental storytelling.

Where to find: Both Kunshikter and Bes Tai Tai are available on Kinopoisk, and the studio’s YouTube channel. The cartoons are in Kazakh with English and Russian subtitles available.

Tasqyn’s comics division stands out as the intriguing part of the studio, as its creators explore stories that manga readers would call either shojo or shonen.

How about some loser and a ghost budding time? Latifa is a writer. At 26, she got out her bestseller and now… well, she got pressured by the publishers to write a sequel and it tanked. Hard. Sinking with it her audience. After that, anyone would need a breather, and Latifa chose the countryside. Little did she know that she would find a company in those backwaters—a ghost girl named Inzhu.

Jastyq Shaq is a slice-of-life slash mystery drama destined for evening reads under the blanket. It revolves around the relationship between Latifa and Inzhu, and if the story gives just a quick flash of how they met, basically living it off-screen, it's the evolution of their views on each other that gets the narrative's gears moving. After all, if Inzhu is a ghost, what is it that happened in her past?

Adamtas is a different story. It starts when a family stumbles upon a fair boy with horns, surrounded by small critters. He doesn’t know who he is or how he became lost in the vast steppe. Even his name, Aman, is given to him by the people who rescued him. Aside from horns — usually adorning Turkic gods — the boy can take on the appearance of other people. The other clue hinting at his identity is a mysterious pendant hanging from his neck, leading him into a world that he must discover as if for the first time.

These two, Jastyq Shaq and Adamtas, seem to offer different perspectives on the coming-of-age narrative, each shaping its own distinct world. What are these cute, Pokemon-like creatures roaming the world of Adamtas? And what about the acute social commentary that the authors behind Jastyq Shaq as they unravel the complexity of the characters?

Where to find: Both comics are available in English and Kazakh on Tapas and Netshards, and are recommended for readers aged twelve and up.

A rider wanders through the hills, passing by sparse boulders. One has a frowning face etched into it, but the rider doesn’t notice; he has other things on his mind. This is Mergen (Мерген), the titular character of a comic book by Magira Tleuberdina, a weary warrior from a time when the Great Steppe was inhabited by creatures eerie yet wonderful.

Mergen returned to a peaceful lot from the battlefield, but its blades had carved deep into his being. Magira wrote his character as that of the antithesis to the masculine hero; someone whom she described as a 'down-to-earth type,' seeking simple things in life. But wherever he goes, there's a constant presence of unresolved conflict—a battlefield he carries within himself, along with a lineage of great warrior ancestors calling for him to act. In a world full of wonder, he is seeking that magic for himself, only to find vicious spirits as restless as he is.

A rider wanders through the hills, coming to a woodside. He almost passes by a lone boulder, but catches himself staring at a frowning face etched deep into the rocky surface. He has ridden past that same boulder so many times, in so many places, but only now has he finally looked at it. The air stills...

Where to find: Mergen is intended for a young adult audience, aged sixteen and up. The first arc spanning four issues is available in Kazakh and Russian.

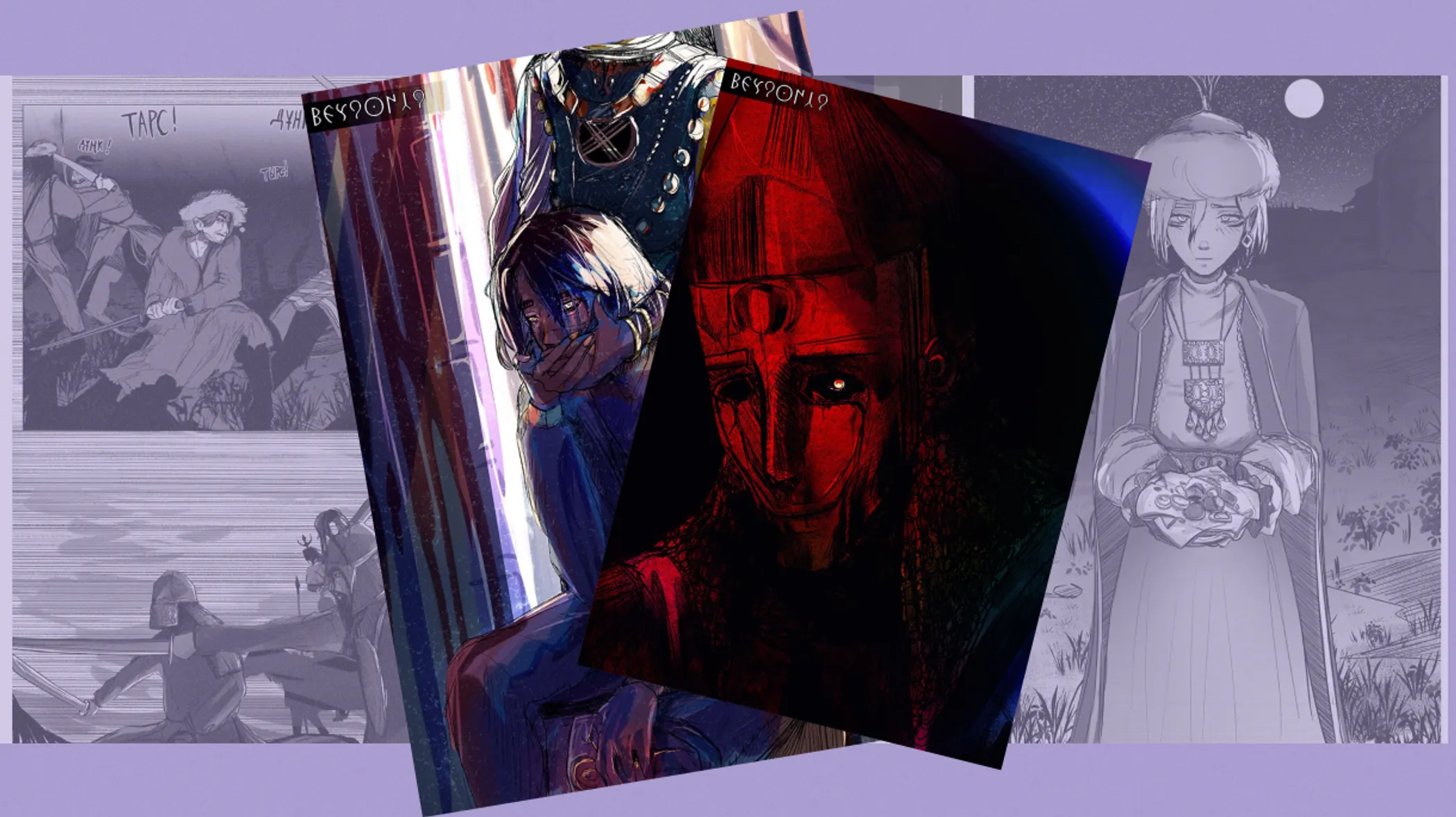

Our final entry for this list is Rinat Akhmediyarov’s Besqonaq, a left-to-right manga that tells the dark tale of Kaysar, a man who was deprived of his own name.

The Great Khan draws near, as the ground shakes under each tumen. The tens of thousands. Through his eldest son, the Khan will become the progenitor of the three-union state that’ll govern this land, but at this moment, it’s but a distant future. For the people of this land are merely a checkpoint before yet another one.

Besqonaq tackles weighty subjects. Its hundred or so pages contain an author's take on the concept of mankurt. A person who was driven to madness, stripped of memories, and conditioned to blindly obey. Perhaps one of the most famous interpretations of this sad reality of the past and the place of origin of the term is Chyngyz Aitmatov’s The Day Lasts More Than a Hundred Years (И дольше века длится день). That novel concludes the story of a mankurt on a bitter note, but Besqonaq explores an alternate scenario — what would happen if an individual desired to reclaim their identity.

Where to find: Besqonaq touches on adult themes and is recommended for readers aged sixteen and up. The first issue is available in Kazakh and Russian.

These aren’t all comic books and animation works worth your time, just those handpicked by the QazMonitor editorial, and we strongly encourage you to go further. There’s much more out there. For example, just this past weekend, the Astana crowd was treated to a new comic book — a high-octane action piece of QATYGEZ by Iskander Adal. The bottom line is that the Kazakh comic books are definitely worth your read. The narratives are becoming more elaborate, visual styles are already diverse enough to cater tastes of many enthusiasts, and the best part is that the local scene is just beginning to unfold.