At the recent COP28 in Dubai, the participants’ group photo underscored a certain narrative. Setting for a grand and long-term goal of transforming the global economy, humanity could muster only fifteen women among the sea of men for a photo-op. A contrast that is only amplified by the fact that an estimated 45% of the world’s social entrepreneurs — people setting up enterprises with the specific goal of driving change — are female.

In Kazakhstan, the disparity between the male-dominated establishment and the female-led grassroots initiatives is even more clear-cut. A first-hand experience with the scene, both on the ground and institutionally, lays this issue bare. “When I talk about social entrepreneurs in Kazakhstan, we see a sort of a similar pattern here,” pointed out Emin Askerov, commenting on the whole debacle with COP28. Askerov runs a social enterprise employing disadvantaged people and serves as the President of the Association of Social Innovators. To him, that group photo in Kazakhstan — the photo-op of local problem solvers — can only be genderbent, featuring only women in the frame.

This was one of the issues discussed at “Impact Central: Bridging Social Development and Entrepreneurship in Central Asia” conference. Organized on February 22–23 by Nazarbayev University (NU) in Astana, the event featured experts from local communities and abroad swapping notes on civic engagement. Attending the event, the QazMonitor reporter took note of some of the numbers and statements:

Only 274 of the supposed fifteen thousand social enterprises in Kazakhstan are officially registered

According to the UNDP, There's a discrepancy between the vocal support for gender equality and the corresponding fund allocation

The investment in people for a social cause makes up for it, creating long-term employee-employer partnerships

To step up and make a profit out of it

The core idea of social entrepreneurship lies in its ability to fill the void where either the government or the market fails or is reluctant to address the needs of the general population.

The data on hand charts that ‘employment void’. Statistics show that 55% of all social enterprises (SEs) in Kazakhstan deal with employment challenges in vulnerable communities. The big number here outpaces ecology topics on the public agenda, as well as inclusive education, medicine, and healthcare. Askerov said these standings don’t really differ among Kazakh cities, as on the surface, their economic structure doesn’t seem to influence SEs' makeup.

This focus on employment is reflected in the law governing the establishment of SEs in the country. Enacted on January 1, 2022, it states that a social entrepreneur is a person who:

Solves employment issues within vulnerable communities, with their enterprise comprising at least 51% of said community

Belongs to a vulnerable community and wishes to establish a business

Provides services or goods to vulnerable communities

Allocates at least 50% of income to improve health and recreation opportunities for children, environmental protection, among other social issues

It is hard to say whether local problem solvers identified a problem out of the public eye. Askerov mentioned that paired to 274 officially registered SEs are an additional fifteen thousand working “in the grey”. Those who drive change but operate as regular business ventures.

On the front of legally-conscious SEs, the capital is in the lead, standing at 74 registered entities, and as Askerov adds, “The trend is weaker in other regions but a lot depends on local executive bodies — the kind of support they provide, how forthcoming they are about these topics.” The expert takes the big discrepancy as a sign of an awareness problem, “It is of great importance to inform about the value of joining the registry.”

A social enterprise listed in the SE Register is eligible to receive:

Subsidized interest rates of 7% for loans up to ₸1.5 billion ($3.3 million) for investment purposes and up to ₸500 million ($1.1 million) for working capital. These loans are issued without sectoral restrictions

Subsidized interest rates of 7% for microloans up to ₸20 million ($44,452) for investment purposes and up to ₸5 million ($11,113) for working capital

Zeroing in on all the clues left by various SEs running their operations would reveal just how limited Kazakhstan’s sample really is. The register run by the Ministry of Digital and Space lists only 166 enterprises [as of April 10, 2024, the list has grown to include 436 registered SEs]. A far cry from those mentioned at the NU conference. Which is somewhat baffling because the government, which maintains the very same register, allocated ₸290 billion, or around $644 million, last year to aid small and medium-sized businesses.

Despite the allocated funds being granted entirely for national entrepreneurship, the unregistered thousands operate within regular legal framework. These businesses may have benefited from the allocated funds and, like any good enterprise, generated a profit. Such is the case with the UK, where the government reports 131,000 SEs across the islands, contributing £60 billion to the national GDP. These figures, ₸34.3 trillion or $76.4 billion, are nothing to sneeze at — they represent about a third of Kazakhstan’s GDP.

SEs specifically differ from nonprofit organizations in this regard. They operate on the assumption that whatever drives social change, makes returns.

How to contribute a third of Kazakhstan's GDP

“We were running deficit. There was a period when I was in the red, and we were happy just to break even,” recalled Gulmira Parmysheva, speaking to the press in the brightly lit hall at NU. For a former NGO worker it was challenging to rewire to even thinking about profit. “I'm actually ready to write a book about all my mess-ups!” she admitted. “The main difficulty was to be prepared to be an entrepreneur. We aren’t taught that — we are taught leadership, team building, psychology.” And nothing about making returns.

It has been five years since Parmysheva’s inclusive workshop, Global Kishkentai, started creating toys for preschool children with disabilities. Wooden boxes on the outside, but as soon as the lid opens, a whole playground is revealed inside. These are educational. Marketed to very niche demographics. So, how do you go from, “I was a weak entrepreneur, a sort of an ‘NGO boss’,” in 2019 to the current “average monthly turnover of ₸12 million ($26,579)?”

Parmysheva’s business occupies market share that one research paper called ‘a key to the development of social entrepreneurship.’ It followed the 2020 survey by the Zor-Rukh foundation, which interviewed 62 respondents from across the country, and distributed questionnaires to 297 representatives of various SEs.

Surveyors then took those answers and averaged them to percentages, breaking it down as follows:

39% provide services

32% abstained from answering

14% produce goods

8% trade goods

4% engage in custom work

3% are classified as "other"

Only 14% establish their own production bases, meaning, as the research paper suggests, many potential SEs can’t take on an order that could potentially recoup their losses and generate profit.

Wooden toys, on the contrary, can be ordered en masse. As Parmysheva shared, “We've grown, and are now in on the production for IT companies, crafting kits for IoT projects.” Since last year, her project has been collaborating with the local startup CodiPlay on programming kits for schoolchildren in Kazakhstan, South Korea, and recently in Saudi Arabia.

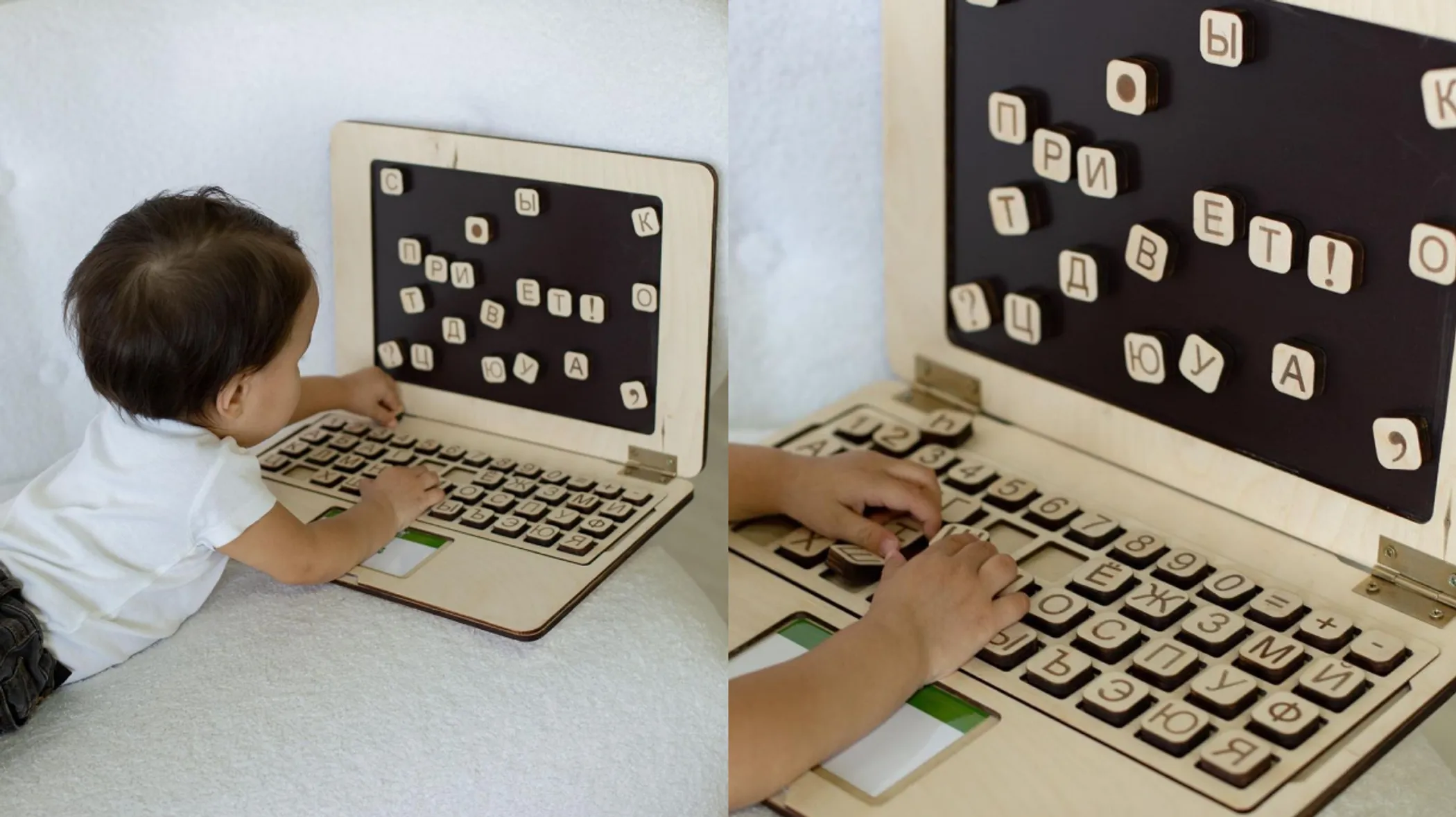

One of Global Kishkentai's sets is a wooden laptop, complete with a magnetic screen for attaching small wooden keys. Crafted at a small people-wise production site, this screen serves as a playground. Syllables, made-up words, and complete sentences all go here. The key selection also comes with numbers, mathematical notations, and punctuation marks.

Played with by children, these toys chain social value creation. Bonds, experiences tying children and their parents to fun memories together. Passed among kids, they connect these small and chaotic communities. However cute, the creation of social value doesn’t start or end there; rather, this loaded and fuzzy concept traces its origins back to the very source – the production site. In our case, it’s an inclusive workshop in Almaty. There, Gulmira Parmysheva executed on what is called Work Integration Social Enterprises, or WISEs. These SEs employ vulnerable communities, and how they go about it is where it all starts.

“Of course, there are challenges to this,” noted Parmysheva on the employee makeup of her enterprise. “If the regular procedure is that I give a week-long probation period, then with disabled people I provide two months for them to adapt.” Her workshop serves as a sustainable ‘sheltered’ medium for the disadvantaged in the local labor market. The latter is often not flexible enough or accustomed at all to the specific rhythm of these people, and this is where Global Kishkentai steps up its game compared to other businesses. A simple change to the employment formula, and the company innovated on its business model and sparked what can be called a convergence of social value and economic value.

This simplicity in innovation is something intrinsic to SE operation; when Parmysheva was speaking to the press, another speaker was addressing the audience of the panel session about the same notion literally a walk away. Professor Satyajit Majumdar from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai recalled an example similar to Global Kishkentai’s case in spirit.

Along the western coast of India, the Mahi River runs past the outskirts of the city of Vadodara and continues on into the Arabian Sea. Local farmers thrived on the river’s bounty, but as fertilizer usage grew year by year, from 7 kg/hectare in 1966 to 135 kg/hectare in the '10s, the land became toxic. Its yields contain residues in water, soil, food. All of it comes back to people with an illness called acute pesticide poisoning.

A local company, Krishi Naturals, works to adress this issue. Their stance on organic farming is what makes their work particularly strenuous. In contrast, local farmers view traditional agriculture as far less productive; many believe that without the chemical input they will run a deficit. These small-scale properties turn to fertilizers as their response to poor yields, which are only exacerbated by climate change, creating a sustained negative feedback loop.

Professor Majumdar pointed out that what Krishi Naturals does to address these worries is simple. They carry out awareness campaigns and link individual farms directly to the city market in Vadodara. Given that farmers already have production sites at the ready, they take on the role of a ‘face’ for those who lack the resources for marketing and distribution. The setup is such that each bottle of ghee, a clarified butter, contributes to the restoration of the land.

Being a drop in the ocean, both Kazakh and Indian SE cases chose to tackle their overarching issues in a way that is manageable and profitable. Profit isn't the sole goal here, as it’s used to fuel meaningful sustained change. Global Kishkentai invested time and resources in disadvantaged individuals, converting what Gulmira Parmysheva termed ‘the hottest investments a business can make’ into a long-term employee-employer partnership. A positive feedback loop, where the SE takes short-term losses for almost little to none staff turnover.

The WISE approach creates a sense of camaraderie in a working environment, establishing a sustainable chain:

Long-term operational losses are cut due to negligible staff turnover

Employed staff receives skills necessary for work and attains sustainable wages

Global Kishkentai expands its operations because the enterprise is financially viable, in turn expanding opportunities for its employees

Gender, unemployment, and the big picture

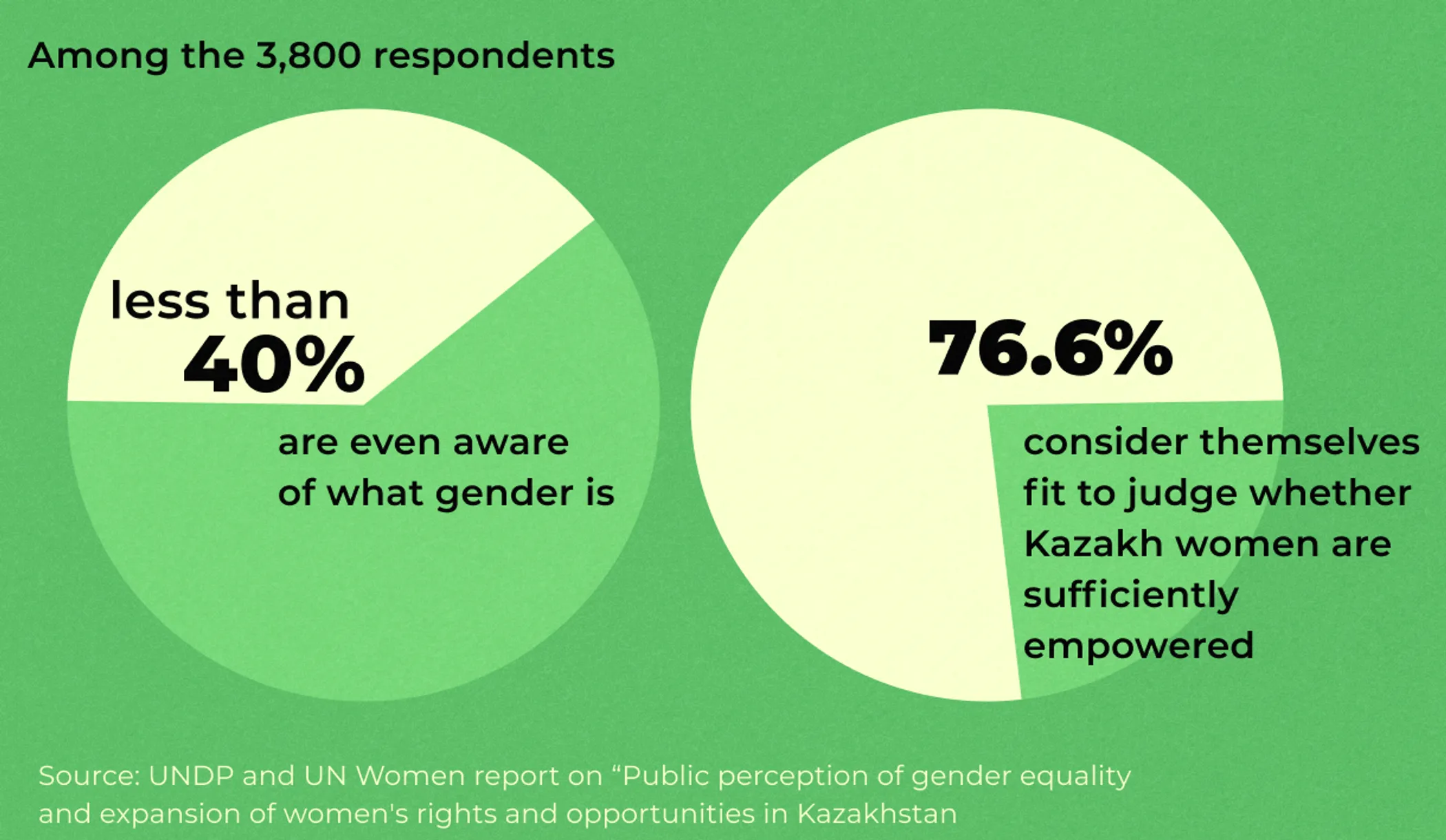

The whys of women's prevalence in Kazakh social movement remain unexplored. But one can make an educated guess. If there are over 90% of SEs in the country being led by women, and the majority of those aid vulnerable communities, then the following stats can tell a potential narrative. Between 33,5% and 39,4% of respondents in Kazakhstan indicated familiarity with terms such as gender, gender equality, women's empowerment, and feminism.

Maybe the answer is simple as, "Those who need it, drive the change,” and given how women in Kazakhstan have doubts not only about their opportunities in general but about basic needs such as personal safety, this feels justified. The correlation in this narrative, of course, is illustrative, a hypothesis drawn from a recent report by UNDP and UN Women. In bold, the text lists disheartening results.

So, the hypothetical point stands on its own — women are at the forefront of social change in Kazakhstan, despite or perhaps because of their disadvantaged position in local society.

“We talk a lot about gender equality, engage in a lot of planning, but how much are we investing real money?” questioned Gaukhar Nursha, addressing the conference. “That is, do we merely pay lip service to gender equality or do we really accumulate funds, invest in this issue, and allocate resources to eradicate the root causes of inequality?” inquired the Gender Specialist at UNDP. Funding is a sore subject for local SMEs in general, and as UN monitoring in Kazakhstan revealed, the sustainable development goal on gender equality (SDG 5) is not included in the republican budget. Meaning, state incentives do not see gender in entrepreneurship.

But what is the big picture? One research paper from 2023 on the matter, argues that women entrepreneurs who embed themselves in local communities are able to better understand and articulate the local context and its issues. That’s because they can bridge gender and any socially-warped production they work with. The locality, the surrounding context, as well as gender sensitivity for women and men, is not lost on them.

At a glance, Kazakhstan seems good on this front. Out of 1.3 million registered individual enterprises, about a half are run by women, yet, the gender pay gap remains. In general, women earn 25.2% less than men. The research sees the problem in Kazakh vocational education, where primary enrollment falls on young men. This dynamics prevents women from vulnerable communities from accessing stable skilled jobs offered by other women.

Echoing the research, Gaukhar Nursha noted that hassle fallout is particularly adverse to women entrepreneurship in rural areas. “Of course, for rural women, it’s difficult to obtain a loan for business due to the illiquidity of housing for collateral,” she shared, weigning care economy — all the unpaid labor that women do for others — as the major obstacle for many women. An issue especially prevalent in rural setting. Heating, housework, and with rural households, this may include fieldwork, livestock care, these all consume a lot of time, and health.

Returning to the paper on women entrepreneurship, it presents a good analysis of three country-by-country cases. Malaysia, Canada, and Sudan, each adressed gender in legislation, yet, the first two compare favorable to the latter. That’s because Malaysia and Canada took steps to advance women’s working rights to a great economical benefit; and just to add, if Kazakhstan were to close the existing gender pay gap, it could increase the national income by 27%. All of this to say, legal framework can go a long way in insuring women's rights, while also chaining positives for economy, SMEs and SEs, and society as whole.

The research details that aforementioned cases speak to clear actions on this front:

Issue a by-law regulating equal rights for women and men, especially in increasing representation of women in politics and leadership positions which will maintain income equality

Involve vulnerable women, such as mothers of large families or single mothers, elderly women, and those raising a disabled child, in social entrepreneurship. The SEs can provide these women with a specific rhythm they need to balance wage and care work

Revise the national Entrepreneur Code with several conditions enabling these women access to whatever education type they need

Maintain and address gender statistics and gender issues in the national Social Code, incentivizing regular and social businesses to focus on more gender-sensitive areas for their entrepreneurial activity

“Well, I, for one, have my gray hairs. I’ve gotten older, but my nerves are where they need to be,” summarized Emin Askerov, reflecting on the past ten years. The first panel session of the conference had come to an end, and now guests and speakers had begun to chat away in the direction of the buffet. “I consider myself one of the ultimate failures among social entrepreneurs out there,” he continued, “Because on my way there, I made a lot of mistakes. But it’s thanks to them that I can now teach others. I caution them that they too will fail, but they have to find the strength to get up and keep going to prove that they can make a difference in this life.” Scaled to actions, these words had Association of Social Innovators host an inaugural Quryltai, a two-day forum in auburn Astana. That November, the capital saw SEs from all Central Asian states swap notes.

Sipping tea after the conference felt a bit different. Guests and speakers formed a line at the buffet, and the high-rise tables in the hall were served by Kunde Cafe, an NU business resident established by one of the former students. The catch is that it is one of the SEs, a WISE, to be precise. Kunde Cafe employs vulnerable individuals, and the makeup of its staff is a stark contrast to every other cafe in the city. That tea wasn’t served by underpaid students whose first jobs were exactly what they feared about adult life, and because of it, its flavor carried a different meaning this time around.